Why governance needs evidence, not intention

The new currency of trust

For regulators, investors, courts, and stakeholders, trust is increasingly grounded in documented outcomes, demonstrably rational decisions, verifiable stewardship, and transparent accountability. Board effectiveness has reached a critical inflection point: tone at the top is no longer sufficient - it must be supported by evidence.

Since 2016, South Africa’s King Codes have consistently promoted a substance-over-form mindset. The shift from “comply or explain” to “apply and explain” reflects a global expectation that governance must be both intentional and demonstrable. Yet PwC’s 29th Global CEO Survey (2026) confirms that the gap between governance intent and operational delivery persists.

The persistent gap: Behaviour without infrastructure

PwC’s survey -- based on more than 4,400 CEOs globally, including over 150 from Africa -- reveals a central paradox. While 81% of African CEOs expect local economic conditions to improve, 59% report no increase in investment and 26% report reduced investment. Optimism, on its own, does not translate into execution.

A similar pattern is visible in governance.

King IV™ (2016) advanced the “apply and explain” philosophy. King V™ (2025), effective for financial years beginning 01 January 2026, sharpens this evolution by:

- reducing the governance principles from 17 to 13

- introducing a standardised Disclosure Framework

- intensifying focus on technology governance, AI oversight, cyber risk, ethical leadership, and sustainability.

Behavioural and ethical expectations are no longer aspirational - they are increasingly structured, testable, and expected to be evidenced.

Despite this progress, many boards still operate in a grey zone. Management reports and dashboards may highlight risks and controls, yet without corroboration, real-time visibility, and clear accountability, directors can inadvertently rely on untested assumptions.

This is rarely a failure of intent. More often, it is a failure of governance architecture.

When culture alone is not enough

Behavioural governance rightly emphasises culture, tone, and psychological safety. These elements remain essential, yet when disconnected from robust systems, they can become fragile. Poorly integrated or siloed governance structures allow assumptions to go unchallenged, assurance to fragment, and compliance to devolve into a box-ticking exercise. Boards then inherit risks they did not create, exposing themselves to regulatory, reputational, and personal liability.

Effective governance demands both the right behaviours and the right infrastructure.

Evidence-based governance: Where culture meets reality

Leading organisations are reversing the traditional sequence. Instead of relying primarily on narrative assurance, they are building environments where evidence precedes oversight.

In practice, this means:

- collective, real-time data input from executives, risk, compliance, internal audit, company secretariat, and prescribed officers

- combined assurance processes that validate information before it reaches the board

- disciplined application of the “nose in, hands out” principle, focused on interrogating evidence rather than accepting narrative.

When governance gaps, actions, and accountability are visible in near real time, boardroom challenge becomes more objective and less personality-driven. Psychological safety improves because inquiry is grounded in shared facts.

Lessons from failure and progress

Steinhoff International remains a sobering example. Its 2017 collapse demonstrated how an experienced board can be misled when oversight relies heavily on persuasive narratives and fragmented assurances rather than corroborated information. Weak accountability visibility allowed irregularities to persist, culminating in significant value destruction and regulatory consequences.

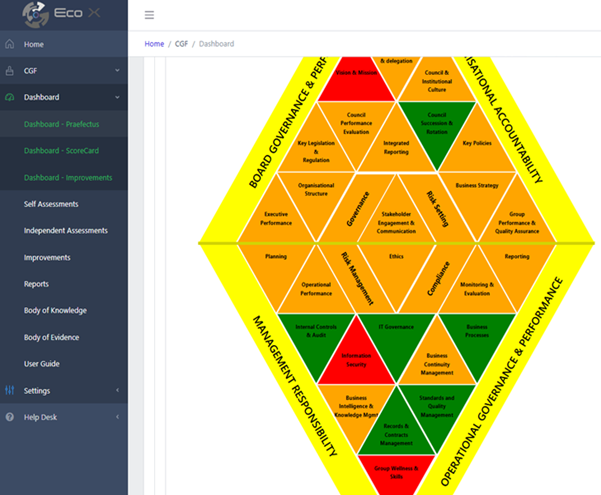

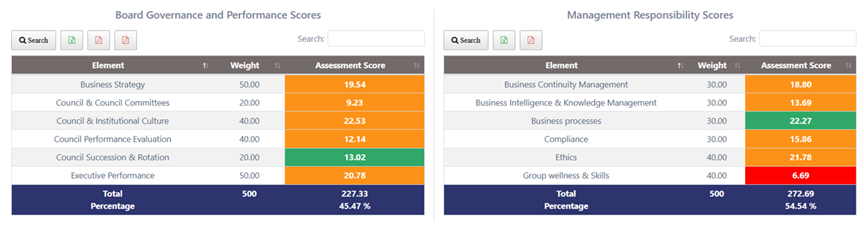

By contrast, organisations adopting mature digitised governance frameworks (DGF) are experiencing a different dynamic. Integrated platforms enable multiple internal stakeholders to contribute to a shared, validated view of governance maturity and risk exposure. Combined assurance becomes continuous rather than episodic.

Where DGFs are augmented by appropriately controlled (non-generative) AI capabilities, organisations can:

- analyse historical decisions

- identify emerging control weaknesses

- stress-test governance thresholds

- detect assurance gaps earlier.

What is a Digitised Governance Framework (DGF)?

It’s a structured digital environment that consolidates risk, compliance, assurance, ethics, and performance information into a continuously validated view, giving leaders real-time insight into their organisation’s governance.

Importantly, this can be achieved without introducing ‘AI hallucination’ risk or unnecessary data leakage. Confidence improves, not because risk disappears, but because decisions are grounded in verified organisational reality.

The AI governance parallel

The same evidence gap is visible in AI adoption. While African CEOs broadly endorse AI, PwC reports that:

- only 41% have a clearly defined AI roadmap

- 37% have formalised responsible AI processes

- only 26% believe current investments are sufficient.

The constraint is not ambition. It is governance readiness - specifically:

- fragmented data environments

- unclear accountability

- weak assurance over information flows.

AI, like governance more broadly, cannot be responsibly scaled without credible evidence foundations.

System-level disruption and the board’s blind spot

DGFs and AI represent genuine system-level disruption. Resistance is understandable, but increasingly risky. Boards that delay the maturation of governance architecture are not protecting their organisations - they are increasing exposure to regulatory scrutiny, assurance failures, strategic blind spots, and reputational harm. The greater risk is no longer technological adoption; it is governance unpreparedness.

Practical questions for Boards

To translate principle into action, boards should regularly ask:

- Where is our source of governance truth?

- What proportion of board information is independently validated?

- How mature is our combined assurance model?

- Do we have real-time visibility of material governance risks?

- Can we evidence ethical culture beyond survey results?

- How effectively is governance embedded?

These questions shift oversight from confidence-based assurance to evidence-based stewardship.

The global imperative

Globally, boards are increasingly judged on the robustness of evidence underpinning decisions, their transparency and accountability discipline, operational effectiveness of governance systems, and demonstrable ethical stewardship. Failure to align these elements invites regulatory sanction and stakeholder mistrust. Conversely, evidence-based governance strengthens oversight quality, supports better decision-making, and builds durable confidence.

Closing reflections

The defining governance question is no longer whether capable directors or well-written frameworks exist. It is whether boards have reliable, verifiable knowledge that enables responsible challenge and sound decision-making.

When behavioural governance is reinforced by robust infrastructure -- including DGFs and controlled AI -- psychological safety becomes more authentic, oversight becomes more resilient, and organisations are better positioned to navigate complexity.

In an era of heightened scrutiny, boards can no longer rely solely on tone, trust, or theory. Evidence is now the language of governance credibility.

As Dion Shango, Territory Senior Partner for PwC Africa, notes in the PwC Global CEO Survey:

“Reinvention isn’t an option - it’s an imperative.”

We agree.

END

Words: 1,004

For further information contact:

Terrance M. Booysen (CGF: Chief Executive Officer) - Cell: +27 (0)82 373 2249 / E-mail: [email protected]

Jené Palmer (CGF: Director)) - Cell: +27 (0)82 903 6757 / E-mail: [email protected]

CGF Research Institute (Pty) Ltd - Tel: +27 (0)11 476 8261 / Web: www.cgfresearch.co.za

Follow CGF on X: @CGFResearch

Click below to read more...